|

|

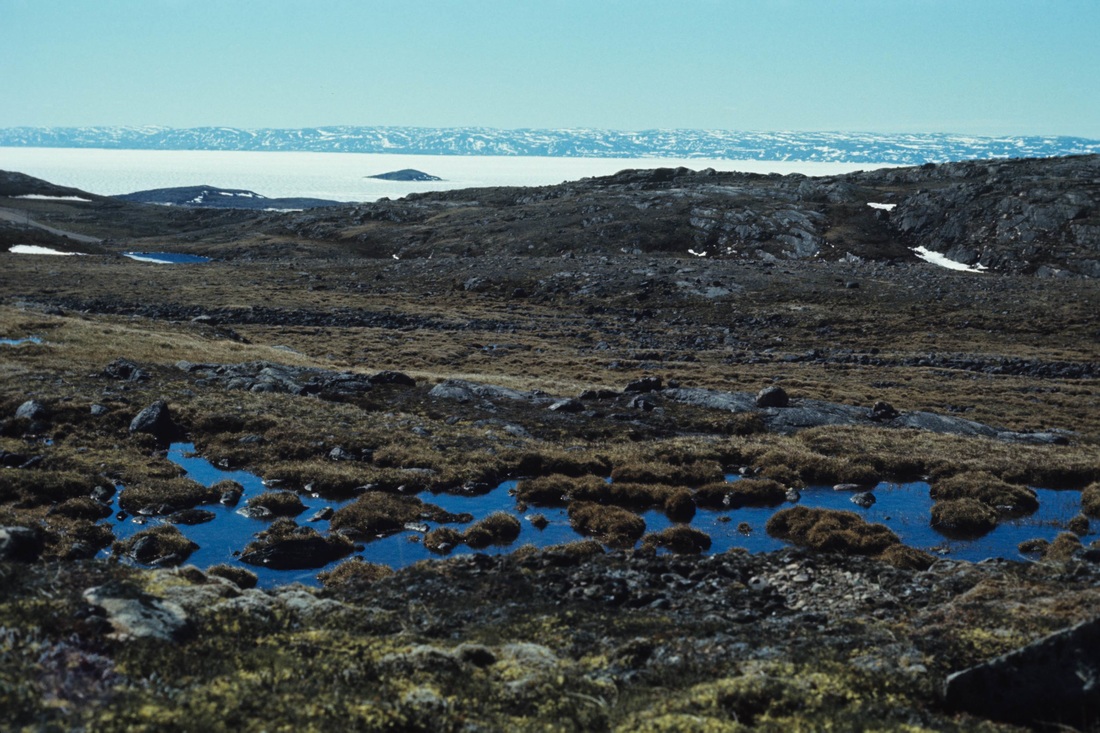

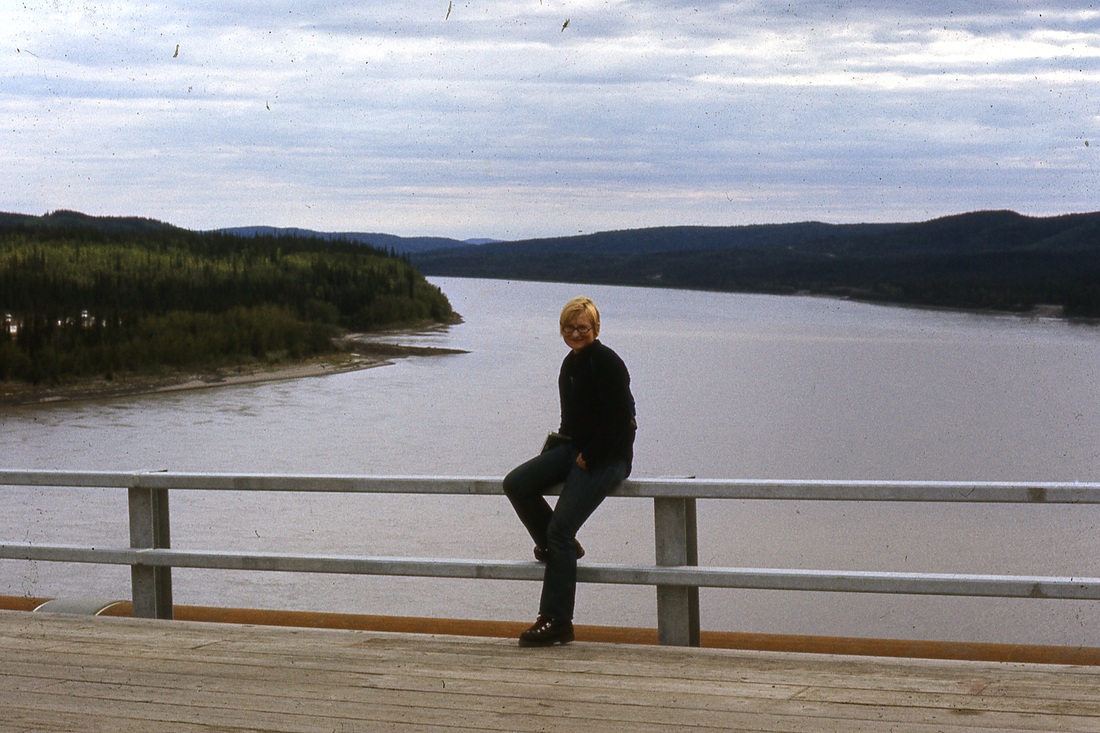

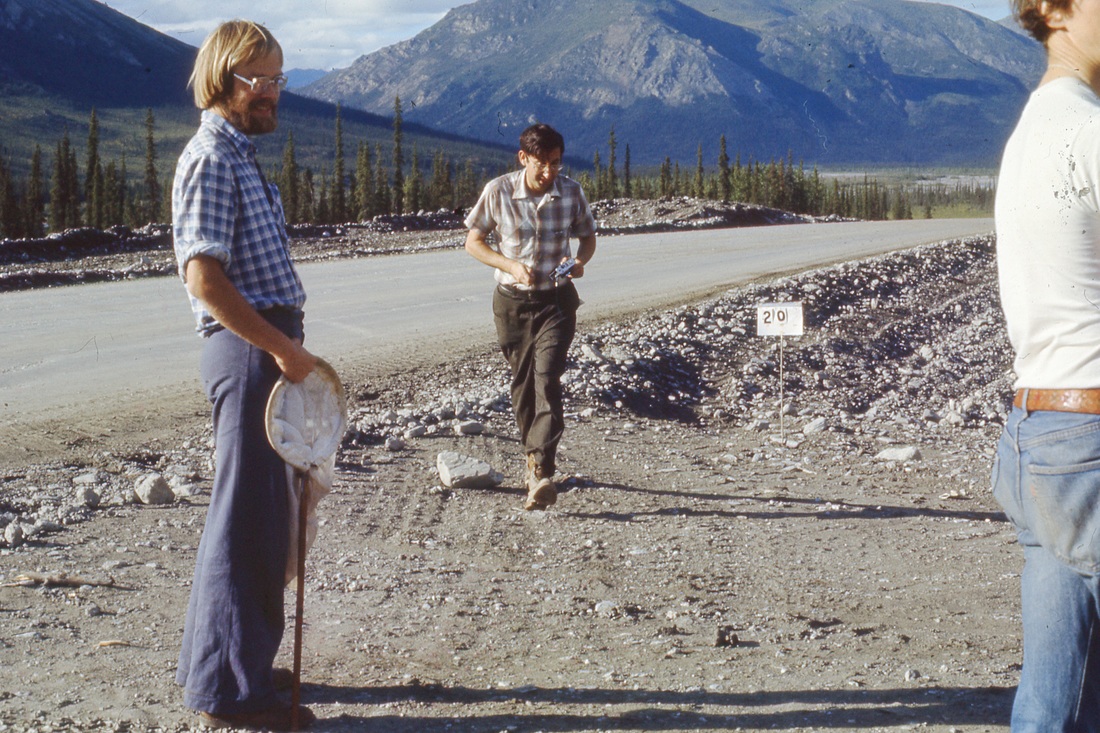

29 July, 1975 It was wonderful being home, especially seeing Guy after so long. But, as I wrote to Mum and Dad – being in Alaska was one of my greatest experiences ever. I felt that I had been shown a marvellous treasure, though I found it hard to explain to anyone that it was worth giving up friends and “the best summer that Montreal ever had” for running around on ocean ice, coming across vividly coloured patches of flowers in seemingly flat, undifferentiated tundra and sitting around at Meade River after midnight listening to the camp’s music – two University of Alaska Profs playing a violin and the bagpipes. There is an addictive smell to the tundra, that of Labrador Tea (Ledum groenlandicum), I wanted to smell it again and immediately started working on returning for the 1976 active season. In September I attended an Arctic conference held in Ottawa, Canada and again serendipity took over. I had been writing to and begging arctic researchers to collect soil samples for me, so that I would have an overall idea of biodiversity in the Canadian arctic. The Arctic Conference was a chance to meet many and thank them personally. And so I met Grace and Monty Wood who would remain colleagues and friends. Monty is a natural teacher – and shares his wisdom easily. I had corresponded with the mite guru, Evert Lindquist, a colleague of Monty’s at the Canadian National Collection of Insects, Arachnids and Nematodes, but had never met him. Monty summarily removed me from an “uninformative” session at the Conference and deposited me on Evert’s doorstep in the K.W. Neatby Building at the Central Experimental Farm with the introduction “Val Behan – she’s interested in mites”. And so began a close collegiality that still continues. Arctic North America 1976 Peter Baril, the CBC reporter stationed in Iqaluit at the time, was my door to the Eastern Arctic of Baffin Island. I knew Peter through Indra Harry, with whom I had shared an apartment when doing my M.Sc. He offered me the first floor of his house for sleeping, setting up extractors and microscope, and so late June 1976, I was off to Frobisher Bay. Somehow it reminded me of Connemara, and so my parents were reassured, especially as I wrote “Mum, I was talking to a 10-year old Inuit kid from here that has never seen a polar bear, so it really is as safe as Connemara!”. I loved the Inuit kids who would politely ask “Can we come and visit?” before coming in and checking mites crawling around under the microscope. I had arranged to use lab. facilities at Iqaluit hospital for preparing media for feeding experiments on the mites and was surprised how well-staffed it was with 5 doctors, 17 nurses and 1 surgeon, and at their kindness tolerating me. Each day I would explore a different path around Iqaluit, collecting mites from different microhabitats, and butterflies for colleagues. I could collect mites no matter what the weather was like, but needed sunny days for the butterflies. At weekends kids would join me telling me the local names for plants and those which they eat. They have adopted me and give me kisses and nose rubs because I make then chocolate-chip cookies! Other weekends I had the company of summer students at CBC or medical students and residents doing their elective in Iqaluit. Through their local girlfriends I learned something of the Iqaluit culture. The Hudson Bay Co. store used to be in Apex rather than Iqaluit, and when boats came with the year’s supplies, Iqaluit residents would rush along the 3 mile sea-side path to Apex to help with the unloading. Peter’s second in command at the CBC station here thinks nothing of taking off after work on Friday on a 14 hour skidoo trip to Lake Harbour to kill skin and clean as many caribou as possible, and then be back in time for work Monday. I’d have loved to talk with the elders but did not speak their language, and it would take a lot longer than my short time staying in Iqaluit to be accepted into their homes. Like all newcomers to a northern town I was shocked by the price of food and what was available. Everything, other than arctic char, seemed to be 3 times the price in Montreal. And the logic of the Arctic Ventures shop having the basics such as flour, soup and soap and 6 types of caviar escaped me. Although stores were waiting for the sea-lift to renew supplies, and had limited amounts of most items, the supply of soft-drinks was amazing, everyone seemed to drink the stuff and people’s teeth suffered as a result. 12 July 1976 I’m off to Igloolik on Wednesday for 5 days and really looking forward to it. Igloolik is a real Inuit village that got established around a trading post, unlike Iqaluit which was started by the US army. Peter Baril went up there for a week covering a meeting of settlement councillors from the Eastern arctic which is taking place there and paying the CBC station there their once-in-awhile visit. He will phone the lab. and tell them I’m coming. Wednesday, left for Igloolik, with over an hour delay at Iqaluit airport. I got talking to an engineering student doing summer work with the Department of Public Works out of Yellowknife. He was flying around the arctic supervising the laying of gravel pads for oil tanks in all the settlements. It was his second trip to Igloolik in so many weeks, and he had been everywhere in the arctic, but he didn’t spend enough time in any place to get acquainted with the locals. He was good company to Hall Beach, on the Melville Peninsula, which is as far as the jet goes. Hall Beach is like the end of the world: a gravel runway, the terminal shed is a quanset hut and there was no food or coffee. Its an old DEW (Distant Early Warning) site. Big coincidence though, going to the honey bucket I recognized one of the passengers - it was Martin Lewis, a Professor of Botany at University of Toronto who spent 2 years as a Botany Lecturer at University College Dublin. I had met him in Fairbanks in 1973 and he is a good friend of Pat Flanagan. He’s the supervisor of three students at Igloolik, and this was his first trip there. He’s a small Welsh man, about 36, who quotes Joyce non-stop. The 14 of us passengers going to Igloolik were fast friends by the time we took the 20 minute flight by Twin Otter over the waters of the Foxe Basin. Igloolik is about 10 square miles, but almost cut in half by a large bay. Its a small settlement of about 700 and is meant to be a model Inuit settlement with good community spirit etc. At this time of the year half the adult population is away hunting so the town is quiet. Phil Mattheis, one of Martin’s students, whom I knew from Meade River, and Andy Rode, the head of the lab. met us at the airport. The lab is amazing - a mushroom shape building, all in white overlooking the town. The stem of the mushroom is the entrance and maintenance, and the head consists of 10 labs and offices opening off a central area. It has a shower and compost toilets. The 360 view overlooks the town and the island. Living quarters are 2 small, 3-bedroom houses in the town close to the lab. As we were 6: Martin, Phil, David, Susan (Martin’s students), Anne, a McGill student and myself, we had one house for the boys and one for the girls, and thus a bedroom to ourselves. Though we ate with the guys because they cooked the best. I was washer-upper in chief. The houses have stoves for heating and cooking, honey-buckets, no running water, but a sink with a drain. We had 24 hours of daylight so no reason to go to bed at any particular time. My routine was getting up whenever and walking different parts of the island collecting mites. Igloolik is high arctic, the highest elevation is about 30 metres and the flora is less diverse than around Iqaluit. It has a long history and the following is from the community’s Website (as of 2015, NOT 1976) “Dorset people lived here 4,000 years ago. Iglulik Inuit are the Iglulingmiut, Aivilingmiut and Tununirmiut people. Their first contact with Europeans was not until 1822, when two British Navy ships wintered in Igloolik. In 1867, the year Canada was born, the American explorer Charles Francis Hall visited Igloolik in his search for survivors of the lost Franklin Expedition. A French-Canadian mineral prospector named Tremblay of the Bernier Expedition visited the island in 1913. In 1921, a member of Knud Rasmussen's Fifth Thule Expedition also visited here. The first permanent presence of southerners came with the establishment of a Roman Catholic Mission here in the 1930s. It had the one-and-only radio in Igloolik. By the end of that decade, the Hudson Bay Company had founded a trading post on the island. Igloolik was one of the first communities in the High Arctic to get other permanent non-indigenous establishments such as the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, day schools and medical facilities.” Friday I went lemming hunting with Martin and Phil on the other side of the island. We got there easily by walking across the intervening ice. We had seal for supper and then we were all going to the Dance - the local Friday night dance. Non-Inuit don’t normally go, but we wanted to be accepted in the community, especially Martin’s students who would be in the community all Summer, so off we want. Nothing started until 1AM, but was continuous dancing once it started up. Martin, Susan and one of Peter’s colleagues, Jens, a Greenlander, and myself danced until 4.30AM. We went back to the guy’s house for tea. Phil and Dave, who had left the dance early because they felt they stuck out (both over 6ft.) were still up and planning to walk over the ice of the Foxe Basin to a nearby island and camp there, and they were including me. Three miles over the ice on July 19th! Jens cautioned against it, saying the sea ice was starting to be dangerous, but Phil and Dave were determined, so I said I’d go along if I had some sleep, but I was not camping over. Saturday was an adventure. Phil brought 2 sleeping bags just in case one of us fell in, though I think you only have 1 minute in seawater at 69N. It took 3 hours to walk the 3 miles to the island because we had to weave back and forth to stay on good ice, with me walking behind the guys. The island is larger than Igloolik and breathtakingly beautiful. The remains of the sod houses that Inuit used are still in a semi-circle around a small church/priest’s house. The house is a one-room affair, about 12ft square. And here a French priest from Brest tried to convert the Inuit. His grave is in the Igloolik cemetery - borne Brest 1896, died Igloolik 1954. I know the Inuit could have done without western religion, but sitting on his couch/bed (wooden), looking out at the frozen sea, I was in admiration of the man’s idealism. What a hard life, having to learn Inuktitut, and compete with the attractions of the Hudson Bay Co., on Igloolik, where eventually the camp and church moved. Everything in this part of the Arctic is safe from looters, and though the Inuit use the house for shelter, as we were doing, everything remains: the old kitchen utensils, honey bucket, fur bed covers, ivory door handle, even some food, an open packet of coffee and the communion wafers in a tin under the bed. Even the Inuit missal was there plus the priest’s light reading - French detective stories. How I wish you were along with us Dad. The house was really a shack, and really poorly built with bad insulation and papered with French comics. It must have been horribly cold in winter. One of the priest’ old jotters was around, and Inuits who had passed by had written down their names. We put our names also. We walked the island for a few hours and climbed to the highest point - about 250m. Coming back was easier, but the wind had opened up more leads. If we had camped overnight, we probably would have needed to wait for a helicopter to rescue us. We arrived back about 11.30PM - 11 hours of solid walking - I was exhausted. An invitation was waiting to come up to the Rode’s house for the evening. The others had gone, so we devoured the supper they had kindly left us and joined the party at about 1AM, Phil inviting the Greenlander Jens, who had dropped by. Andy makes homemade beer which is the only booze in town (Igloolik is dry). Martin who drinks quite heavily was well on the way to being drunk. Andy and his wife, who’s a nurse in Igloolik have been in the north for 15 years, and in Igloolik for 6, but tend to stay removed from the Inuit, so bringing along Jens, who is Greenland ‘Inuit’ was a social error. However, as we had to bring Martin home carefully, everything passed okay, so we finally got to bed at 4.30AM. What a day. August 2, 1976 Dear Mum and Dad, I’ll be going to Alaska August 11 as the pipeline trip has been moved until August 14th, and we will be going to Prudhoe Bay and back. I’m glad as this will give me a breather between the Iqaluit and Fairbanks trips. I won’t be able to send or receive mail while on the pipeline, but otherwise my address will be: c/o Prof. S.F. MacLean Jr., Irving Bldg., University of Alaska, Fairbanks, Alaska 99701 Fairbanks, August 21, 1976 At long last I’ve the chance to write about everything that has happened in the meantime. I was met at the airport by Steve MacLean, who whisked me off to a Department picnic, where I met those going on the pipeline trip: Steve himself, Arne Fjellberg, a Collembola expert from Norway and Jerry Brown who organized the funding for the trip by the US Army Corps of Engineers (called CREEL). He is involved with organizing a lot of biological research in the arctic. He’s married to a nurse from Dublin and is a real dote, but has a terrible reputation for being able to keep tabs on everyone working in the arctic at the same time. People receive messages from him seemingly out of nowhere. One senior Professor, doing research 7 miles out on the tundra from the nearest research station, felt he had escaped Jerry at last; but saw a plane circling overhead from which dropped a tin can containing a note from Jerry! Thursday - We went to the Alyeska (Consortium building the pipeline) headquarters in Fairbanks to have our ID pictures taken for the pipeline and were issued with a carte blanche ID allowing us food and accommodation everywhere. I thought we were going to be camping, but Steve has a bad back and wanted to sleep in a bed as much as possible, and definitely didn’t want to cook along the road. Friday - We got started about 10AM. We had an almost brand new station wagon for the 4 of us, but it had already done a pipeline trip and the windscreen was heavily pockmarked; our trip would add many more. I had brought along chocolate and apples thinking that we would go all day without food, but we stopped for lunch at a construction camp, and so the routine started. Breakfast was wherever we spent the night; lunch in a camp along the pipeline and dinner usually where we spent the night. We stopped in Livengood for coffee and donuts and had out first introduction to a pipeline camp: 20-30 trailers attached to each other formed the living quarters and all around are tire shops, maintenance shops, sewage shops, generally looking like an enormous scrapyard. We were sweeping vegetation for insects on the way north and then doing soil sampling on the way south - at least that was the general plan. As you can imagine three adults wielding butterfly nets caused much amusement. For example, Pump Station 6 is a hard-hat area and also had an interesting revegetation plot that we decided to sweep, with hard-hats on, of course. Walking over to the plot, some workers called out “going to catch a bear with those, are you?”. We thought they were just being funny until a large black bear came wandering over towards us - the local bear, and my first. He/she took no notice of us and went off in search of blueberries. There is now a bridge over the Yukon, until this Spring everyone had to be ferried across. I suppose a bridge over the mighty Yukon heralds the end of a ‘last frontier’ era. They were putting the pipe across, so we could only cross when the men were going for dinner. Of course we were sweeping trees along the southern banks of the Yukon in front of all the traffic waiting to cross the bridge. As you can imagine, sweeping to much amusement and cat-calls. When the bridge opened to traffic, we and everyone else was rushing to 5-Mile Camp for dinner, and we had our first introduction to pipeline camp dinners - superb. The evening menu was: pea-soup, prawns, steak, scalloped potatoes, fresh asparagus, mushrooms, about 5 different salads and 5 different desserts. We all ate as though we had been doing a hard days work! We also saw three black bears rummaging around the back of some trucks. We were agape, but no-one else paid them any heed. We spent the night at Old Man Camp. Camps where you can stay are just like really good university residences. There are men-only trailers and women-only trailers, but there is much coming and going during the night. There are free laundry facilities, and loads of showers - real luxury on a field trip. Trucks doing the Fairbanks - Prudhoe route can do it in 18 hours, so we could have been travelling much faster, except that Jerry Brown was logging the road. That is, he would stop at the intersection to every Material Site (MS) and every Deposition Site (DS) along the road, take its name and mileage and a photo of the north and south facing aspect of the intersection. All good, except there is an MS and DS at least every 2 miles. After about the 20th stop it was beginning to be tedious and amusing. three of us would hop out of the car and be photographing gorgeous scenery and Jerry would be photographing gravel edges. And all gravelled edges looked the same. We couldn’t help laughing, and Jerry got the point, and so continued with the mileage and name logging but took less photos. Had lunch today at Pump Station 5, because security at Prospect Camp had recommended the food. The men at Pump Stations are in general ‘hard men’, there to do a job and no messing. As well, Pump Stations are permanent fixtures on the pipeline and will remain after the construction camps go. From Coldfoot Camp onwards we were in the foothills of the Brooks Range and around Dietrich - Chandalar we passed “the most northern white spruce along the pipeline” = treeline. In this area there is a stand of white spruce and from here on north only willow, birch and alder grows. Somehow it is more momentous than crossing the Arctic Circle marker, we are now really in the Arctic. Near Chandalar we saw our first and only grizzly - a mother with a very playful cub. I was thrilled, we were about 100yds from them and right next to the car. We stopped for dinner at Chandalar, which is a lovely Camp. The name comes from “Gens de L’air” which is what the French called the natives in these parts. They had an electronic pingpong game and Arne and myself played. We’re equally matched, so played at every other camp we visited. We crossed Atigun Pass, the highest point on the pipeline and then on to Toolik Lake. Antigun Pass is an area where the pipeline is behind schedule and making a horrible mess of the landscape. The sides of the Pass are very steep and caterpillar machines working the slopes need to be tied to stationary caterpillars in case they get out of control. They need to get a gravel bed down to support the pipeline, but with permafrost the gravel just melts and the gravel base runs off into the river as silt. They must avoid silting the river, so they need to build huge gravel dams at the base of these slopes to hold back the silt. For this they need to gouge more gravel from the hillsides leading to more melt! The Pass area is the ugliest so far along the pipeline, though we did see a wolf. And so onto Toolik Lake Freshwater Station where we were staying overnight. I had spent a few days there in 1975. Now the camp was enlarged, they had a trailer and 2 campers. There were 10 researchers, some of whom I knew from the previous year - a great crowd. They are on excellent terms with the pipeline camp up the road and can go there for showers and laundry. They gave us mattresses to sleep on and for the first time I unrolled my new sleeping bag, good to -15C. I was dying for the opportunity to try it.The researchers at the camp had some hair-raising stories about grizzlies. They had a regular Saturday night visit from a local grizzly for 2 months. Most of the researchers are camping in tents and one girl recounted waking to this enormous dark shape outside her tent. The grizzly flattened her in the tent and started to roll her around in it, with her trying to make herself as small as possible under the sleeping bag. The bear finally moved off, perhaps annoyed by her screams. She rushed to the nearest truck, locked herself in and sounded the bear horn. Luckily she wasn’t hurt but what a frightening experience. Another fellow got out of his tent in the morning to have a grizzly standing in front of him .In sheer shock he tried to fight his way back into the tent, blocked by his tent mate who said “Get out of my way - I want a picture”. It was funny hearing the tales, but must have been frightening at the time. I was glad to be sleeping in the trailer. Went for a swim with Steve in Toolik Lake, and nearly passed out with the cold. He just dived in. I must have shrunk a whole size and certainly all the dust of the previous day fell off me. Later we drove to Franklin Bluffs camp. The pipeline is meant to be buried for most of this part, but as they found that the pipeline people had been passing poor welds, or falsifying the X-ray data, they had to dig up about 1500 welds - an expensive repair. At Franklin Bluffs I met an Irish girl from Castlebar, about my age, who had nursed in England and then moved to Alaska with her husband. She was making some quick money on the pipeline as a bullcook, i.e., cleans bedrooms, changes sheets etc. She said that there were a number of Irish at Franklin Bluffs. She was saying that they’re not allowed outside the camp, even for short walks, on pain of firing; this is because of bears. None of them gets to travel the Haul Road like us, because each Camp has its own airfield. Finally we reached Prudhoe which stretches about 8 miles and there are camps and drilling rigs scattered everywhere - its ugly. We had lunch at Pump Station 1 and then decided we needed to check out the BP Hilton which got a write-up in National Geographic. Its a permanent hotel for BP people working at Prudhoe. Its 3 stories high, has a heated swimming pool, leather armchairs, and the main attraction, an indoor patio with tall birch, oak, maple trees, tomato plants and petunias, to make the lads feel at home. The patio looks out of place, especially when you realize that the trees outside are no more than 2” high. As Jerry was meeting someone, we were allowed to wander around, feeling rather incongruous in our felt-line boots and dusty clothes. We started our soil sampling at Prudhoe Bay and returned to Franklin Bluffs for another night. There’s an Alyeska checkpoint on the Haul Road at the Yukon Bridge and just entering Prudhoe. At both places they check ID cards, trip ticket for the truck, and all the official papers. They can also check for alcohol, as the camps are meant to be dry, though I never saw so many tipsy people in one place as Monday night at Franklin Bluffs where they were having a party. Jerry was paranoid about the no-alcohol stipulation, so we didn’t even have beer with us. Tuesday we picked up Dr. Vera Komarkova at Prudhoe. She had just completed her Ph.D. at U. Colorado, Boulder and I had met her the previous summer at Meade River. She is a superb botanist, so a perfect addition to our group. We also dropped off Jerry, who was driving down the Haul Road with a group of Engineers. Although his physical presence was removed from the car, our paths criss-crossed down the Haul Road and we got notes when we didn’t see him in person! We went then to climb the largest pingo we could find in the Prudhoe area. We had scoped one out the previous day; about 35m high and about 5 km from the Haul Road hiking across tussock tundra - possibly the toughest walking conditions known. I was really disappointed to find when we got there that the Corps of Engineers stopped there on their helicopter trips into Prudhoe and had left their tin cans around. We were sampling daily now, collecting soil samples at regular intervals. On the Thursday we decided to climb to a permanent snow-bed to collect arctic-alpine mites and collembola. Quite an experience for me, as I was the least in shape; Vera is a renowned mountaineer with the Himalayas and peaks around North America in her mountaineering CV. Arne is Norwegian and so has a natural tendency to walk uphill, and Steve is built like a mountain goat. I just had determination. Steve, Vera and I put on long-johns, but Arne, wisely just carried his. I had to strip down to T-shirt and jeans not far into the climb. We finally got to the snow-bed and it turned out to be a small glacier - fantastic. Steve tried to walk on it, fell through a bit and was able to jump out before falling through completely. We still had the peak of the mountain looming about us. Arne was carrying the sandwiches and 4 beers and he was not doling out those until we got to the peak and so up we went. This unnamed mountain is 7000ft high, and we named it Budweiser Mt., for collecting records and for the wonderful taste of the beer at the top. The view from the top was magnificent, we had a 360-view from the top of the Brooks Range, with its snow-covered peaks and glaciers, just spectacular. Well if climbing up the mountain was hard, coming down was murder. Half way down with the load of samples on my back my ankles and knees had turned to jelly. It took an incredible act of will-power to get my legs to walk in a straight line. We got back to Antigun Camp just in time for dinner and then onto Chandalar camp to stay the night. There we all had a sauna and sweated ourselves to relaxation. Friday my legs were in agony - every step was crippling. Vera and Arne were fine, but Steve was a bit quiet. We were sampling between Chandalar and Old Man Camps and Arne went off to climb another hill, promising me all kinds of wonderful mites if I joined him, but it was an effort to get out of the car much less walk another slope. We stayed that night in Old Man Camp, Jerry was at Old Man Camp also, so we were all together one last time. We worked our way back to Fairbanks on Saturday, back through a taiga landscape, all of us really sad to be leaving the arctic. We had only 2 flats on the trip, no other problems and seemed to be bringing back half the tundra in samples, which we’ve been working through 16 hours a day since. Fairbanks was a bit of an anticlimax after the Haul Road. Vera and I couldn’t get space in the Residence so we shared a trailer with Arne, a mixing of the sexes highly disapproved of by the Director of the Institute of Arctic Biology. It suited us grand, as we could cook for ourselves. Steve was going home to his family so left us with the truck which I could drive having a licence. We decided to go for a beer to celebrate our homecoming, but I met a fellow I knew from the previous year who persuaded us to go to a party given by a guy going up for election. I was a bit wary, but the others were eager, so off we went. And yes, it was a fund-raising party, $5 entrance, but with fantastic food. The politician was he who had written the Bill which made marijuana legal in ones own home in Alaska. The party was in a beautiful log home overlooking Fairbanks and you can imagine the scene. All the characters there were very cool and there was loads of good food, drink and hash. Arne and I gate-crashed, pointing out that we couldn’t vote; Vera paid as she believed in the guy. The whole evening was great, Vera was in her element and Arne was vacillating on whether or not to try hash for the first time Vera left for Hawaii, we left her to the airport and I will miss her. Her giggles on one hand and incredible botanical knowledge on the other were an integral part of the trip. Later over beer, I almost had Arne crying on my shoulder - he’s only married 8 months, and it is his first time away from his wife who is 3 months pregnant, and he’s remaining here until the end of September. Steve and family are living in a tiny apartment until their new house is built, and so have no space to entertain. Fairbanks can be tough for those by themselves who are working there for a short time. Students and staff go home in the evenings and so you are on your own evenings and weekends, unless you love going to bars. Another evening I went for dinner to the Flanagan’s - Pat and Tina, the couple I visited in Galway at Christmas. They’ve been back in Fairbanks since February and are really glad to have left the university political scene in Ireland. They’re a fantastic pair and are living in a beautiful cedar and pine house they built for themselves about 4 miles outside Fairbanks. There was a volcano expert there also, and a French woman, battling leukaemia and her children. Great evening; its lovely hearing Pat’s brogue along the corridors at the University and Tina was at Beaufort when I was at The Abbey, though a couple of years ahead of me. Got back to the Residence about 2.30 to be up again at 4AM to leave Steve and Arne to the plane for Meade River and Barrow. They just came back from there in time for us to have a last evening together. And so an incredible summer is over. If anyone asked me “Where to go? What to do?” I’d say “go to Alaska”. If you can stand the weather its a place where even dreams come true. |