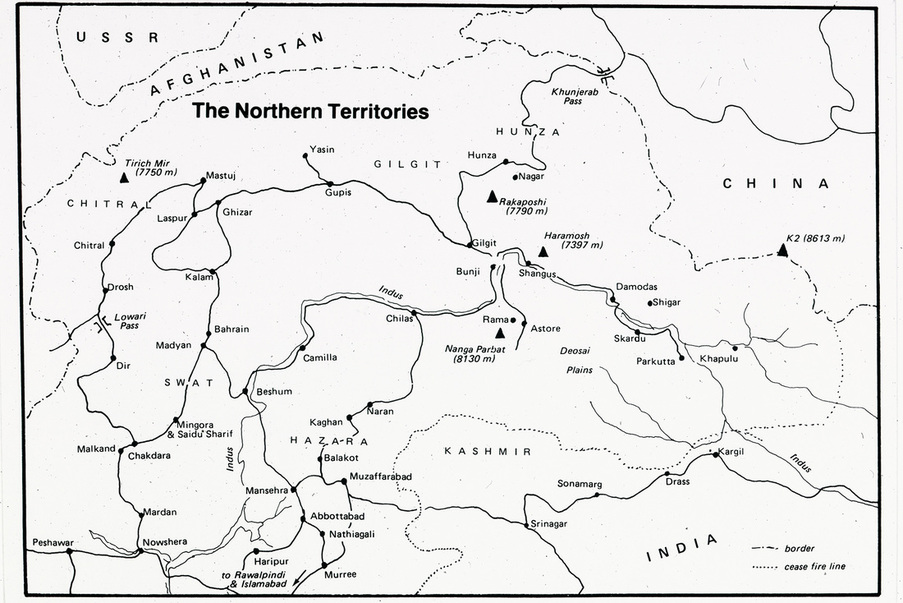

In 1986 I was an Assistant Professor at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. After five years in the department, my tenure document had just been submitted. There wasn't much more I could do, so I took a vacation. A few months earlier I had read an article in the New York Times about the Karakroam Highway in northern Pakistan opening up to foreigners. So I decided to go to Pakistan and travel up the KKH, as it was called by those in the know. Lonely Planet had a sketchy guide book to the area. I got a cheap flight through a 'Bucket Shop' in London, and headed off. I didn't keep a journal. However, I wrote a few letters to my parents and asked them to make a copy for Val. She found those letters recently and returned them to me. What an interesting trip! I also found some old slides and have included them too (most are at the end of this post).

Scroll to the end for more photos.

28 August 1986

Dear Mum and Dad,

Well, even in Shangri La, eating is not going to be a gourmet event. This is the first meal I have dared to order, and I'm still apprehensive about eating it. So, what's it like? Mum, I'm glad you're not here because you'd be appalled at times (as I am), by how incredibly primitive it is. But Dad, you would be in your element (as I am often), at stepping back into the Middle Ages. I'm serious about Shangri La, for I am in the Hunza Valley, about 100 miles south of the Chinese border, a fertile, terraced heaven-on-earth, hidden in the midst of the Karakoram Range, towered over by Mount Rakaposhi at 25,500 ft., a breathtaking peak. This valley of the Hunza River, stretching about 10 miles over three tiny villages, is considered to be the model for Shangri La because people live to a great age here (to their 100s). It's said that their age reflects their diet - fruit mostly in summer, as they grow apples and apricots and walnuts, and in winter rice, bread and little meat. They don't have much fat in their diet, water is mountain-clean, and unlike the rest of the country, they have a local wine, which they consume. The country is very Muslim in general and so booze is utterly unavailable, but they are followers of the Aga Khan, and so are more liberal with themselves, I suppose.

There's just so much to tell that I don't know where to begin. Let me start by describing the 'scene' here. I'm in Karimabad, one of the three villages in Hunza, accessible only by four-wheel drive, and a narrow one at that, as it's some 2 kilometers up off the main road, the Karakoram Highway. It's about 8 PM and I've been asleep for three hours, taking a well-needed nap as I was on a bus for almost 24 hours from Rawalpindi to get here. So instead of eating at my hotel (what a euphemism), I decided to try a place up the road. It's a 25x30 ft. room with about eight Formica tables, concrete floor, lit by a gas lantern. There's always a sink and tap, or in this case a dry sink, as Muslims are very particular about washing their hands before eating. There's no menu, so I ordered beef, rice, bread and Coca Cola and tea (pre-milked and usually pre-sugared, but in this case the sugar is optional; the milk could be buffalo, goat - probably not cow). Needless to say, playing it safe you cannot drink the water. Indeed, I've been told to avoid meat too. Dinner consisted of a bowl of lukewarm rice (white), a bowl of beef curry (gingerly I ate a little), a chapatti or flat, pancake-like piece of bread, and a cucumber and onion salad (ignored). When I came in, there were about six old men here drinking tea, who ignored me pleasantly. A little later two German fellows came in. They are sitting at another table making no overtures, so neither am I except to nod. The proprietor watches over all. But as I watch him now, he's picking his teeth with a fork destined for the next customer, no doubt, and while the men were here, they routinely spat on the floor. This is just the tiniest description and I have so much else to tell. But at any rate, as per Val's warnings, I take two megavitamins each day, try to eat a piece of fruit (peeled), drink as much prepared liquid as I can, and stay healthy. I'll take a bet I'll lose 5-10 lbs. on this trip though, which suits me fine, actually. Just to complete the picture of this restaurant, there are flies, fans on the ceiling, but stopped as it is about 60 degrees. The daytimes up here at 8,000 ft. are a pleasant, sunny 75 degrees and at night it can drop to freezing, but has not done so far. Back in Rawalpindi it was over 90 degrees each day, which I found difficult to tolerate, let alone enjoy, so I made a dash for the mountains.

Let me go back to my arrival and tell you about the first couple of days, and then, if you don't mind, I'll get you to photocopy this letter and send one copy to Val who will send one to Anne Hong (for she is my alter-ego travelling companion, the one I would have most enjoyed with me on this adventure, though I must admit, the shock of seeing one blond-haired female travelling alone would have been compounded by Anne's presence). They are amazed at a single woman travelling alone. In Islamabad/Rawalpindi, people are strictly Muslim and are either totally covered in a burka - the black shroud with the grille to look through, or at least wear a shalwar kamize - baggy trousers, a tunic and a veil which can hide the face if men look upon them. They have seen Westerners, but still I was an object to be stared at long and hard. Then, further north in Gilgit, the main town of the North West Frontier Provinces, they have seen climbing expeditions so I was less of a nine-day wonder. But still people ask where my husband , boyfriend, friends are. Finally here, the women are still veiled, but seem more open, and I only caused a stir at the hotel when I asked for a single room.

But back to the flight. It was Saturday last. My god! I feel it was a century ago. We were meant to be repaving Phil's driveway but that was postponed. So I piddled around at home (thinking on the cabin now is like thinking about a dream world, so remote is it from this), bade a fond farewell to Sol and Ralph and to Linn on the phone, and dropped by Phil's. He was there with Ron and Art, so we went to lunch and Ron's wife, Maureen, joined us. Then I went back to Phil's briefly, to be surprised by a call from Barney and Fiona. They were at the airport, just back from South Africa, and with an hour still to spare before the bus to O'Hare, I collected them. I brought them back to Ron and Maureen's who had their car while they were away. Maureen took me to the Greyhound, keeping my car for 3 weeks. What an urban, cosmopolitan, travelled bunch we are!

The Chicago-London leg on British airways was one-third full, comfortable and enjoyable. I arrived in Heathrow around 10 AM and had six hours, but by the time I had checked baggage through, there a lot less, too little to leave the airport. It was Sunday, and Terminal 4, the new international terminal was just that - international and thronged. I slept a little, read a little, and tried to look up some old friends like Cliff Rainey, the artist friend of Doc's who we used to stay with years ago in the Reilly days. And Nick, a dentist, from Trinity College Dublin. But no luck. I'll try again on the way home. Then the flight was called and my adrenalin began to flow. Almost everyone, it seemed, was Pakistani, and an amazing mixture. I'd say one third were women, all traditionally dressed, even the English-born ones. The men ranged from young boys, through 20-year olds, to very old men. The former, I expect, were being brought home for a vacation, proudly, by their fathers, to arrange future marriages. The latter would have been brought to England by relatives for summer, illiterate (85% illiteracy in the country!), and with nothing to do there either except go to the park or watch TV uncomprehendingly, and now returning for a more tolerable Winter. Because the flight was direct to Islamabad, a more rural, northerly clientele was noticeable. It's the capital city, but in reality is a diplomatic haven, a newly constructed 'Brasilia' that is utterly remote from neighboring real life. It was a Jumbo jet and full! What a hilarious journey. I pity the crew, as the passengers are a tough lot to wait on. Most don't understand rudimentary rules, like no smoking, fasten seat belts, etc. Then, in flight, the men are constantly on the move, to the toilets, up and down the aisles to chat with friends (everyone knows everyone), while the women never budge from their seats - amazing bladder control. There were three Pakistani stewardesses, and they helped. But by all accounts they are high born, lazy, and despise the 'scum'. Ironically, the 'scum' despise them too, particularly the men, for being paid servants, and un-Muslim. There are stories of passengers trying to cook on primus stoves in the aisles, so you can imagine what an horrific task the crew have. At least in this direction, all of the passengers have seen a toilet. In the other direction it's not the case! Half way through the flight, the flight engineer was called to come back and fix a toilet door, which had been pulled off! (I know. I was in the cockpit when the request came. But more of that later).

I was sitting beside a 35-year old Pakistani doctor, army-educated here, who went to London for six years subsequently. He was returning to Lahore to practice, and was impeccably turned-out, obviously richly-born, and condescending towards his fellow passengers. But he was a mine of information, particularly about Muslims, and the North West Frontier Provinces and the Karakoram Highway where he had been stationed as an Army doctor for three years.

About half way through the flight the captain came around, right to the back of the plane where I was trying to get to the toilet (they're not too good about queuing). I had heard him make an announcement earlier and thought he was from Belfast (it was a British airways flight), so I asked him. He was a Scot actually, but we had a good conversation and I mentioned I was a pilot. He invited me up to the cabin during the movie, and I jumped at the opportunity. Wow is all I can say. We were, at the time I visited, flying a very tightly controlled route over Russia, the Urals, and almost over Moscow. It's the shortest route, and BA is one of the few airlines that use it. The captain, co-pilot and engineer were marvelous, entertaining, informative and quite intrigued at my escapade. I must have asked the right questions as they asked me would I like to come back again for the landing. I could have died and gone to heaven right then! Short of being back seat in a navy jet landing on an aircraft carrier, I can imagine no better fun. So back I went for a couple of hours sleep. But even on the flight, one got the feeling of being a second class citizen amongst the Pakistani men. And it's a feeling that permeates the country, but is obviously striking only to a westerner. However, it makes you THINK if nothing else, and consider other ways. Here I am in a country (USA) that recently announced that women over 35 had a better chance of being attacked by terrorists than of getting married, career women that is. I'm so accustomed, at least in my profession to being respected, admired and listened to by my male peers. But here I am trash, and even less than that because I am unwed, immoral by Muslim standards. Fortunately their distain only extends to a feeling, and they wouldn't touch me, or probably try to take advantage of me. It's safer than I thought, oddly enough. But they certainly stare!

The landing was perfect, a long figure eight, VFR approach to the airport that lies just outside Rawalpindi, about 15 miles from Islamabad. the land is low, scrubby, with outlying villages, patches of green, middle-eastern looking. the crew work hard for that last half hour. I was impressed, as I just sat behind the Captain, following along with everything. What an incredible experience, sitting on top of 350 tons at 250 mph. It was the first time he'd been to Islamabad too!

We landed, and the military presence was obvious - F16s hiding in the camouflaged sidings off the runway. We taxied to the terminal, and I was on my own again. Waiting inside, amidst chaos, for baggage, I got chatting to a Canadian, 26-ish, a refrigeration specialist, and a 19-year old whose parents live in Islamabad, returning for the final year at school, who loathes the place - a very precocious American bird. Then my luggage came. I changed some money, braced myself, and walked out of the airport!

There must have been a thousand people milling around outside, all male, all staring at me, it seemed. So I latched on to the Canadian and asked him how to get to the holiday Inn. It's the most expensive, exclusive hotel in Islamabad, but then again, for my first night... He doubted they would have a vacancy. But he had reserved a room just for the day, and was willing to give it to me for the night (it was 7 AM now). The plane crew was there and greeted me laughingly, and also the other Canadian. The crew got rooms immediately, but the rest of us had to wait about three hours. (I'm learning to add hours, days or even weeks to any estimate of time here - efficiency is not a priority!) We drank tea and watched high society Pakistan wandering through the lobby, as well as others, like a fellow who was carrying a toilet seat - for what I'll never know, but it was incongruous and funny to watch him. By the time the room was ready I wasn't sleepy, so I headed off walking to the American Embassy to look up this fellow whose brother works in the Vet. School. That was a hot (95 degrees), sweaty, 4-mile mistake, as he didn't even work there. But I got a ride to the place he did work, USIS, the PR part of the State Department. He's an English language advisor - teaches key people how to best teach it. He turned out to be a laconic gem. By the time I had found him, jet lag was creeping up mercilessly, so I arranged to meet him that evening and went back to the holiday Inn to sleep. (Of all the things I thought I'd never need, a swimsuit was one, and of course they had a glorious pool at the Holiday Inn). John left me 500 Rupees for half the room, about $25 apiece. It's about ten times more expensive than the place I am staying now, but such are extremes.

That evening Tom Miller picked me up and took me out to an excellent restaurant. He speaks Urdu fluently, having lived in India and Pakistan a total of three and a half years, and writes it too, probably better than anyone else in the state Department. He's married to a Greek woman and they have 2 children. They've been in Islamabad for a year and while his wife and kids spend summer in Greece, they are still contemplating whether another 2 years is possible. I went back to his (palatial, 6 servants!) house for dessert, and a drink, as it's an utterly dry country. He was full of interesting tales, warnings, etc., and definitely took it upon himself to look after me for his brother's sake. He insisted I buy a local outfit - sexless, but cool actually! You'd laugh to see me in it. I went back to the hotel and was woken an hour or so later by the co-pilot and flight engineer to come to their room for a drink. they had called earlier to take me out to the British club for dinner but I was out. The laugh was that they couldn't get room bar service, so we ended up drinking sprite. They were great, though, and wished me masses of luck for the trip.

The next day at noon Tom picked me up and we went to his house for lunch: curry, salad, rice and fruit, all cooked and washed carefully so I could eat it all. They have a water filter and boil water too. Then I just sat around for the rest of the afternoon at his house, mostly sleeping. I woke to a monsoon rain, torrential and windy like a hurricane, but it ends with everything cool and clean and fresh. We ate, drank and chatted more, and arranged a taxi for 7 AM the next morning for me to get to the airport to try to get a flight to Gilgit, the main town for the north. Got a ticket OK, but the flight was cancelled due to weather. It goes by Nanga Parbat (>26,000 ft.) and is meant to be spectacular, but flies as often as not because of the terrain. Found three other foreigners in similar straights - a Dutch fellow, about 28, and two English guys (22-ish), so I latched on to them. This was their second cancelled day and they elected to take a minibus instead. We got a taxi back to Rawalpindi, got refunds on our tickets, and were brought to the minibus place. Waited there for about 4 hours - the English fellows ate, but Rudi (Dutch) and I were hesitant with a 12-hour bumpy ride ahead. Rightly so, too, for they crammed 15 people into a 5-year old Bedford van - with windows - most of whom smoked incessantly. To the accompaniment of loud Arabic music, we bumped and rattled our way off towards the foothills of the Himalayas.

The scenery quickly improved, but the driving habits are perilous. They will try (and fortunately, succeed) anything, at breakneck speed, on sinewy, winding, precipitous roads with utter abandon. Yet you don't see dead cars at the bottom of these gorges, so presumably it's safe! The bus stopped every 2-3 hours or so, to get a drink and piss. But it was impossible to sleep. Just at dark we stopped at a town about half way. Well, shall we say a main street, in the mountains. None of the four of us ate, and Peter, one of the English fellows had been throwing up regularly too. God, We were tired! I had been awake since 3 AM and the others since 5 AM. We continued on, at least a little cooler now, but you couldn't see anything, just feel the bumps and the corners. We travelled in convoy with another minibus - I don't know if it was for security in case of breakdowns or ambushes, as the tribal people are still a law unto themselves. By now I was managing to sleep, but only a little. Finally we arrived in Gilgit at 4 AM, 16 hours later, and as nowhere was open, just slept as best we could in the bus. The driver wrapped a blanket around him and slept on the luggage rack on the roof. With dawn I had decided Gilgit had nothing for me and I was continuing on. The same bus was going to Hunza at 7AM and it would take two hours. Rudi and the English fellows decided to stay a night. So at 8:30, myself and a family of four from Karachi left in the minibus for Hunza. We got there at noon. See what I mean about time! That was the most incredible trip though. Visually it was spectacular with towering snow-capped peaks and green, terraced valleys, colorful, friendly people, and everywhere the driver stopping and picking people up on the road to give them a ride a few miles (free) or many miles (cheap).

We stopped at a roadside stall where they were slaughtering a cow, and the driver bought fresh meat. Thunderous streams were coming down from the mountains, and I agreed to eat a local peach offered to me after being washed in one of these. Two men were sawing a log with an ancient saw; a pig or goat skin was hanging, full of something; a log fire was burning at an outside kitchen with a cauldron of tea, milk and sugar steaming on it. They were baking big flat bread there, and kids, chickens and people milled around happily. It was wonderful.

We wound upward and upward on the Karakoram Highway, and I understand now what an engineering achievement it was (and is, to maintain), for it is carved out of rock and almost daily suffers rockslides. They say that one Pakistani and one Chinese life were lost for every mile.

So finally I arrived, hiked up the mile or so to Karimabad from the road, found an hotel, and slept.

I'm writing this at 8:30 the next morning and already could fill another 10 pages. But I'll mail this - send a copy to Val and she'll send a copy to Anne.

It's wonderful!

Love,

Mary

28 August 1986

Dear Mum and Dad,

Well, even in Shangri La, eating is not going to be a gourmet event. This is the first meal I have dared to order, and I'm still apprehensive about eating it. So, what's it like? Mum, I'm glad you're not here because you'd be appalled at times (as I am), by how incredibly primitive it is. But Dad, you would be in your element (as I am often), at stepping back into the Middle Ages. I'm serious about Shangri La, for I am in the Hunza Valley, about 100 miles south of the Chinese border, a fertile, terraced heaven-on-earth, hidden in the midst of the Karakoram Range, towered over by Mount Rakaposhi at 25,500 ft., a breathtaking peak. This valley of the Hunza River, stretching about 10 miles over three tiny villages, is considered to be the model for Shangri La because people live to a great age here (to their 100s). It's said that their age reflects their diet - fruit mostly in summer, as they grow apples and apricots and walnuts, and in winter rice, bread and little meat. They don't have much fat in their diet, water is mountain-clean, and unlike the rest of the country, they have a local wine, which they consume. The country is very Muslim in general and so booze is utterly unavailable, but they are followers of the Aga Khan, and so are more liberal with themselves, I suppose.

There's just so much to tell that I don't know where to begin. Let me start by describing the 'scene' here. I'm in Karimabad, one of the three villages in Hunza, accessible only by four-wheel drive, and a narrow one at that, as it's some 2 kilometers up off the main road, the Karakoram Highway. It's about 8 PM and I've been asleep for three hours, taking a well-needed nap as I was on a bus for almost 24 hours from Rawalpindi to get here. So instead of eating at my hotel (what a euphemism), I decided to try a place up the road. It's a 25x30 ft. room with about eight Formica tables, concrete floor, lit by a gas lantern. There's always a sink and tap, or in this case a dry sink, as Muslims are very particular about washing their hands before eating. There's no menu, so I ordered beef, rice, bread and Coca Cola and tea (pre-milked and usually pre-sugared, but in this case the sugar is optional; the milk could be buffalo, goat - probably not cow). Needless to say, playing it safe you cannot drink the water. Indeed, I've been told to avoid meat too. Dinner consisted of a bowl of lukewarm rice (white), a bowl of beef curry (gingerly I ate a little), a chapatti or flat, pancake-like piece of bread, and a cucumber and onion salad (ignored). When I came in, there were about six old men here drinking tea, who ignored me pleasantly. A little later two German fellows came in. They are sitting at another table making no overtures, so neither am I except to nod. The proprietor watches over all. But as I watch him now, he's picking his teeth with a fork destined for the next customer, no doubt, and while the men were here, they routinely spat on the floor. This is just the tiniest description and I have so much else to tell. But at any rate, as per Val's warnings, I take two megavitamins each day, try to eat a piece of fruit (peeled), drink as much prepared liquid as I can, and stay healthy. I'll take a bet I'll lose 5-10 lbs. on this trip though, which suits me fine, actually. Just to complete the picture of this restaurant, there are flies, fans on the ceiling, but stopped as it is about 60 degrees. The daytimes up here at 8,000 ft. are a pleasant, sunny 75 degrees and at night it can drop to freezing, but has not done so far. Back in Rawalpindi it was over 90 degrees each day, which I found difficult to tolerate, let alone enjoy, so I made a dash for the mountains.

Let me go back to my arrival and tell you about the first couple of days, and then, if you don't mind, I'll get you to photocopy this letter and send one copy to Val who will send one to Anne Hong (for she is my alter-ego travelling companion, the one I would have most enjoyed with me on this adventure, though I must admit, the shock of seeing one blond-haired female travelling alone would have been compounded by Anne's presence). They are amazed at a single woman travelling alone. In Islamabad/Rawalpindi, people are strictly Muslim and are either totally covered in a burka - the black shroud with the grille to look through, or at least wear a shalwar kamize - baggy trousers, a tunic and a veil which can hide the face if men look upon them. They have seen Westerners, but still I was an object to be stared at long and hard. Then, further north in Gilgit, the main town of the North West Frontier Provinces, they have seen climbing expeditions so I was less of a nine-day wonder. But still people ask where my husband , boyfriend, friends are. Finally here, the women are still veiled, but seem more open, and I only caused a stir at the hotel when I asked for a single room.

But back to the flight. It was Saturday last. My god! I feel it was a century ago. We were meant to be repaving Phil's driveway but that was postponed. So I piddled around at home (thinking on the cabin now is like thinking about a dream world, so remote is it from this), bade a fond farewell to Sol and Ralph and to Linn on the phone, and dropped by Phil's. He was there with Ron and Art, so we went to lunch and Ron's wife, Maureen, joined us. Then I went back to Phil's briefly, to be surprised by a call from Barney and Fiona. They were at the airport, just back from South Africa, and with an hour still to spare before the bus to O'Hare, I collected them. I brought them back to Ron and Maureen's who had their car while they were away. Maureen took me to the Greyhound, keeping my car for 3 weeks. What an urban, cosmopolitan, travelled bunch we are!

The Chicago-London leg on British airways was one-third full, comfortable and enjoyable. I arrived in Heathrow around 10 AM and had six hours, but by the time I had checked baggage through, there a lot less, too little to leave the airport. It was Sunday, and Terminal 4, the new international terminal was just that - international and thronged. I slept a little, read a little, and tried to look up some old friends like Cliff Rainey, the artist friend of Doc's who we used to stay with years ago in the Reilly days. And Nick, a dentist, from Trinity College Dublin. But no luck. I'll try again on the way home. Then the flight was called and my adrenalin began to flow. Almost everyone, it seemed, was Pakistani, and an amazing mixture. I'd say one third were women, all traditionally dressed, even the English-born ones. The men ranged from young boys, through 20-year olds, to very old men. The former, I expect, were being brought home for a vacation, proudly, by their fathers, to arrange future marriages. The latter would have been brought to England by relatives for summer, illiterate (85% illiteracy in the country!), and with nothing to do there either except go to the park or watch TV uncomprehendingly, and now returning for a more tolerable Winter. Because the flight was direct to Islamabad, a more rural, northerly clientele was noticeable. It's the capital city, but in reality is a diplomatic haven, a newly constructed 'Brasilia' that is utterly remote from neighboring real life. It was a Jumbo jet and full! What a hilarious journey. I pity the crew, as the passengers are a tough lot to wait on. Most don't understand rudimentary rules, like no smoking, fasten seat belts, etc. Then, in flight, the men are constantly on the move, to the toilets, up and down the aisles to chat with friends (everyone knows everyone), while the women never budge from their seats - amazing bladder control. There were three Pakistani stewardesses, and they helped. But by all accounts they are high born, lazy, and despise the 'scum'. Ironically, the 'scum' despise them too, particularly the men, for being paid servants, and un-Muslim. There are stories of passengers trying to cook on primus stoves in the aisles, so you can imagine what an horrific task the crew have. At least in this direction, all of the passengers have seen a toilet. In the other direction it's not the case! Half way through the flight, the flight engineer was called to come back and fix a toilet door, which had been pulled off! (I know. I was in the cockpit when the request came. But more of that later).

I was sitting beside a 35-year old Pakistani doctor, army-educated here, who went to London for six years subsequently. He was returning to Lahore to practice, and was impeccably turned-out, obviously richly-born, and condescending towards his fellow passengers. But he was a mine of information, particularly about Muslims, and the North West Frontier Provinces and the Karakoram Highway where he had been stationed as an Army doctor for three years.

About half way through the flight the captain came around, right to the back of the plane where I was trying to get to the toilet (they're not too good about queuing). I had heard him make an announcement earlier and thought he was from Belfast (it was a British airways flight), so I asked him. He was a Scot actually, but we had a good conversation and I mentioned I was a pilot. He invited me up to the cabin during the movie, and I jumped at the opportunity. Wow is all I can say. We were, at the time I visited, flying a very tightly controlled route over Russia, the Urals, and almost over Moscow. It's the shortest route, and BA is one of the few airlines that use it. The captain, co-pilot and engineer were marvelous, entertaining, informative and quite intrigued at my escapade. I must have asked the right questions as they asked me would I like to come back again for the landing. I could have died and gone to heaven right then! Short of being back seat in a navy jet landing on an aircraft carrier, I can imagine no better fun. So back I went for a couple of hours sleep. But even on the flight, one got the feeling of being a second class citizen amongst the Pakistani men. And it's a feeling that permeates the country, but is obviously striking only to a westerner. However, it makes you THINK if nothing else, and consider other ways. Here I am in a country (USA) that recently announced that women over 35 had a better chance of being attacked by terrorists than of getting married, career women that is. I'm so accustomed, at least in my profession to being respected, admired and listened to by my male peers. But here I am trash, and even less than that because I am unwed, immoral by Muslim standards. Fortunately their distain only extends to a feeling, and they wouldn't touch me, or probably try to take advantage of me. It's safer than I thought, oddly enough. But they certainly stare!

The landing was perfect, a long figure eight, VFR approach to the airport that lies just outside Rawalpindi, about 15 miles from Islamabad. the land is low, scrubby, with outlying villages, patches of green, middle-eastern looking. the crew work hard for that last half hour. I was impressed, as I just sat behind the Captain, following along with everything. What an incredible experience, sitting on top of 350 tons at 250 mph. It was the first time he'd been to Islamabad too!

We landed, and the military presence was obvious - F16s hiding in the camouflaged sidings off the runway. We taxied to the terminal, and I was on my own again. Waiting inside, amidst chaos, for baggage, I got chatting to a Canadian, 26-ish, a refrigeration specialist, and a 19-year old whose parents live in Islamabad, returning for the final year at school, who loathes the place - a very precocious American bird. Then my luggage came. I changed some money, braced myself, and walked out of the airport!

There must have been a thousand people milling around outside, all male, all staring at me, it seemed. So I latched on to the Canadian and asked him how to get to the holiday Inn. It's the most expensive, exclusive hotel in Islamabad, but then again, for my first night... He doubted they would have a vacancy. But he had reserved a room just for the day, and was willing to give it to me for the night (it was 7 AM now). The plane crew was there and greeted me laughingly, and also the other Canadian. The crew got rooms immediately, but the rest of us had to wait about three hours. (I'm learning to add hours, days or even weeks to any estimate of time here - efficiency is not a priority!) We drank tea and watched high society Pakistan wandering through the lobby, as well as others, like a fellow who was carrying a toilet seat - for what I'll never know, but it was incongruous and funny to watch him. By the time the room was ready I wasn't sleepy, so I headed off walking to the American Embassy to look up this fellow whose brother works in the Vet. School. That was a hot (95 degrees), sweaty, 4-mile mistake, as he didn't even work there. But I got a ride to the place he did work, USIS, the PR part of the State Department. He's an English language advisor - teaches key people how to best teach it. He turned out to be a laconic gem. By the time I had found him, jet lag was creeping up mercilessly, so I arranged to meet him that evening and went back to the holiday Inn to sleep. (Of all the things I thought I'd never need, a swimsuit was one, and of course they had a glorious pool at the Holiday Inn). John left me 500 Rupees for half the room, about $25 apiece. It's about ten times more expensive than the place I am staying now, but such are extremes.

That evening Tom Miller picked me up and took me out to an excellent restaurant. He speaks Urdu fluently, having lived in India and Pakistan a total of three and a half years, and writes it too, probably better than anyone else in the state Department. He's married to a Greek woman and they have 2 children. They've been in Islamabad for a year and while his wife and kids spend summer in Greece, they are still contemplating whether another 2 years is possible. I went back to his (palatial, 6 servants!) house for dessert, and a drink, as it's an utterly dry country. He was full of interesting tales, warnings, etc., and definitely took it upon himself to look after me for his brother's sake. He insisted I buy a local outfit - sexless, but cool actually! You'd laugh to see me in it. I went back to the hotel and was woken an hour or so later by the co-pilot and flight engineer to come to their room for a drink. they had called earlier to take me out to the British club for dinner but I was out. The laugh was that they couldn't get room bar service, so we ended up drinking sprite. They were great, though, and wished me masses of luck for the trip.

The next day at noon Tom picked me up and we went to his house for lunch: curry, salad, rice and fruit, all cooked and washed carefully so I could eat it all. They have a water filter and boil water too. Then I just sat around for the rest of the afternoon at his house, mostly sleeping. I woke to a monsoon rain, torrential and windy like a hurricane, but it ends with everything cool and clean and fresh. We ate, drank and chatted more, and arranged a taxi for 7 AM the next morning for me to get to the airport to try to get a flight to Gilgit, the main town for the north. Got a ticket OK, but the flight was cancelled due to weather. It goes by Nanga Parbat (>26,000 ft.) and is meant to be spectacular, but flies as often as not because of the terrain. Found three other foreigners in similar straights - a Dutch fellow, about 28, and two English guys (22-ish), so I latched on to them. This was their second cancelled day and they elected to take a minibus instead. We got a taxi back to Rawalpindi, got refunds on our tickets, and were brought to the minibus place. Waited there for about 4 hours - the English fellows ate, but Rudi (Dutch) and I were hesitant with a 12-hour bumpy ride ahead. Rightly so, too, for they crammed 15 people into a 5-year old Bedford van - with windows - most of whom smoked incessantly. To the accompaniment of loud Arabic music, we bumped and rattled our way off towards the foothills of the Himalayas.

The scenery quickly improved, but the driving habits are perilous. They will try (and fortunately, succeed) anything, at breakneck speed, on sinewy, winding, precipitous roads with utter abandon. Yet you don't see dead cars at the bottom of these gorges, so presumably it's safe! The bus stopped every 2-3 hours or so, to get a drink and piss. But it was impossible to sleep. Just at dark we stopped at a town about half way. Well, shall we say a main street, in the mountains. None of the four of us ate, and Peter, one of the English fellows had been throwing up regularly too. God, We were tired! I had been awake since 3 AM and the others since 5 AM. We continued on, at least a little cooler now, but you couldn't see anything, just feel the bumps and the corners. We travelled in convoy with another minibus - I don't know if it was for security in case of breakdowns or ambushes, as the tribal people are still a law unto themselves. By now I was managing to sleep, but only a little. Finally we arrived in Gilgit at 4 AM, 16 hours later, and as nowhere was open, just slept as best we could in the bus. The driver wrapped a blanket around him and slept on the luggage rack on the roof. With dawn I had decided Gilgit had nothing for me and I was continuing on. The same bus was going to Hunza at 7AM and it would take two hours. Rudi and the English fellows decided to stay a night. So at 8:30, myself and a family of four from Karachi left in the minibus for Hunza. We got there at noon. See what I mean about time! That was the most incredible trip though. Visually it was spectacular with towering snow-capped peaks and green, terraced valleys, colorful, friendly people, and everywhere the driver stopping and picking people up on the road to give them a ride a few miles (free) or many miles (cheap).

We stopped at a roadside stall where they were slaughtering a cow, and the driver bought fresh meat. Thunderous streams were coming down from the mountains, and I agreed to eat a local peach offered to me after being washed in one of these. Two men were sawing a log with an ancient saw; a pig or goat skin was hanging, full of something; a log fire was burning at an outside kitchen with a cauldron of tea, milk and sugar steaming on it. They were baking big flat bread there, and kids, chickens and people milled around happily. It was wonderful.

We wound upward and upward on the Karakoram Highway, and I understand now what an engineering achievement it was (and is, to maintain), for it is carved out of rock and almost daily suffers rockslides. They say that one Pakistani and one Chinese life were lost for every mile.

So finally I arrived, hiked up the mile or so to Karimabad from the road, found an hotel, and slept.

I'm writing this at 8:30 the next morning and already could fill another 10 pages. But I'll mail this - send a copy to Val and she'll send a copy to Anne.

It's wonderful!

Love,

Mary

Unfortunately I don’t have the second letter I wrote to my parents. So tales of my travels to the Kunjerab Pass and the Chinese border are missing. Also missing are the negotiations to hire a jeep to go from Gilgit to Chitral over the Shandur Pass, and how I found two French couples (Jean Louis and Claire, Alain and Karin) with whom I could travel safely.

Recently, however, I found a letter I wrote to a friend in Madison about parts of the trip including traveling to the Kunjerab Pass. I also came across a letter I wrote to Rudi, a Dutch man I met and traveled with for several days. These letters fill in some of the details.

Passu

~ 100 miles south of the Chinese border

Dear John,

You have to come here! Yesterday I was alone, utterly alone in a sage desert saddle between two glaciers at about 10,000 ft. there were lizards and birds, but no other sounds except an occasional falling rock. I kept parading a list of people through my mind who might fit into this setting and had no success for a long time ‘til your name wandered through. You’d have been just fine. You will love northern Pakistan, for everything — its incredibly primitive ingenuity, its desolation, its rawness and magnificence, its isolation. There’s a book by Galen Rowell, a pictorial guide to the Karakoram, and I think the title is “In the throne room of the Mountain Gods”. I used to think that was a very pretentious title but no longer. It’s perfect because you feel awed.

I’m writing this sitting on the steps of a tiny inn on the side of the Karakoram Highway, high in the Hunza Valley. There’s a glacier behind, and its run-off rushes by the side of the inn. There are sunflowers and chickens in the garden, warm sun flowing down and a breeze. I wait, neither patiently or impatiently, for a bus going south. You get accustomed to waiting and not fretting about schedules. Most people here that I meet are going to or coming from china. Most have months or even years to travel. I cannot help but envy them. Yet I am just meandering around and perhaps smell fewer daisies, but can do so more fully.

Some two hours later

In that little space a jeep came down the highway and took away the 2 Canadians and the Dutch fellow I have been travelling with. Shortly afterwards a couple of army vehicles stopped and out got the French Alpinist instructors and their students that I had met a couple of days earlier. They had even let me climb with them. A rare feat for Pakistanis. Finally the bus came. I suppose it was neither early nor late, but it was certainly full. You cannot imagine these buses but I will show you photos when I come back. They are rounded and have a more-than-full roof racks (I spent an hour travelling on one of those roof racks a few days ago and it was the bus trip of a lifetime!). the buses are also covered in colored inscriptions both inside and out, so they look like something out of a carnival. They have 3seats and 2, but the aisles are also filled with bags that serve as seats, and people still stand. There is never such a thing as a full bus. It costs $1.25 to travel maybe 70 miles but takes 3 hours or so. First the road is a series of hairpins, and often fords rivers of glacier melt. Then the bus stops everywhere, and finally it stops so that passengers can take tea. This is a ritual, observed about every 3 hours, and since the bus left the Chinese border this morning, its 3-hour break is now. Every man piles out of the bus and the women stay. They have a chapatti brought to them, but modesty dictates that they do not mingle with the men. I am exempt, being the only other female on the bus, and a foreigner, but I chose to stay and write. I’m not in the humor to be stared at this morning. Yet there are 3 little girls lined up outside the open bus window watching every move I make. Now men wander back towards the door, so tea must be over. There’s much hawking and spitting and probably pissing but I cannot see that.

Golden Peak Inn, Gilgit

This reminds me of a youth hostel from the late 60’s except there are no rules. It’s a real “Restaurant at the end of the Universe” place where you meet every conceivable sort of traveler. Sitting in the walled garden, just watching people arrive and depart is utter entertainment, drinking green tea and swatting flies. There is no such thing as a single room, and the dormitory bed is 20 rupees or $1.25. There are double rooms of course. Ah well, such are the disadvantages of travelling solo. But they are few.

I must tell you of using your sewing kit.

(Note to reader: John gave me a clever little Patagonia sewing kit before I left Madison)

You’ll be disappointed to hear that the awl was not involved. Instead I used all of the colored thread except the pink and black. I knew you would be pleased. Now, there’s appoint to this story. I found your brother Tom, and he was as wonderful as you described. I’ll spend much more time telling you about him when I return, but for the present, he insisted that I couldn’t venture north in American dress. He was genuinely concerned, as its certainly off the Holiday Inn trail. So the first evening I met him, he insisted that I buy a shalwar kameez or local female garb. It consists of incredibly baggy pants and a top, and a cummerbund to draw the pants tight! Then there’s another “thing” like a shawl behind which you hide the remaining two inches of exposed flesh on your body, plus your face. We had a limited choice: one with short sleeves through which my tits showed, and one at last three sizes too large, but definitely demure. So he recommended the latter. I gave in gracefully, making a mental note to never be seen dead in it, but later, en route, decided to do a massive renovation. I can still fit 3 babies into the pants besides myself, as bridging the gap (see dotted line) goes beyond even your sewing kit. But now I show a daring inch of wrist, ankle, and the shirt part covers my knees. Mother Carmella (God Bless her!) would approve.

If your brother knew the half of it….

(Note to reader: there’s a drawing of the shirt and pants with a dotted line indicating the vast expanse of gusset in the pants.)

This is the final letter I wrote to my parents. Sadly, the first page is missing.

The bread was about 1” thick and maybe 14” in diameter, made of brown flour, and evenly thick all round. Judging by the crust, it had been baked on both sides. It was excellent too. While waiting for it, we watched a carpenter and a tailor at work, both pretty young fellows, and we were watched in turn by a slew of kids. I couldn’t help being reminded of Ireland about 1830 or so, where you would be treated to tea and bannock in a cottage with clay floor, thatch, and minimal everything else, but equal warmth and curiosity. They use turf here too, and donkeys and creels. The kids have catapults.

Past Mastuj, 7 September, 1986

What an incredible and bizarre evening. We arrived at Mastuj around 2 PM and were shown to the Tourist Cottage by a nice man. It was a walled garden and had only one usable room, but Claire and Jean Louis planned to put up their tent. Suddenly another man appeared, shouting vociferously and it appeared that he was expecting relatives from Chitral later that evening and wanted the cottage. (I’m sure they never came!) So the nice man offered to evict his family for the night and give us his house. He brought us to it, to see if we wanted it, and with a 6-hour drive to Chitral and no other real houses along the way, we accepted. He suggested 5 Rupees each for the bed, and said he’d have rice and chapattis for dinner for us. By this time I had a fever, a sore throat, and didn’t care a whit. He had a 15-year old daughter make tea for us, and we sat around looking desultory and uncomfortable, listening to Chitrali sitar music.

It was a really interesting house, built of mud walls and poles supporting a mud-over-lattice roof. But above the fireplace was a conically shaped log arrangement leading to a chimney. Cooking was accomplished by a paraffin stove, rather like an old camping stove. Goods (so very few) were kept in a chest, along with a few memorabilia, and the dishes were neatly arranged against the back wall. There was a door with a curtain over it, another with an actual wooden door that I never saw closed, and an adjacent room/shed. The main room had two charpoys and he produced three more shaky ones, which he propped up outside, on large mats, and a wee table. The floor, except for near the cooking circle, was covered with dusty mats and cushions, and he put spreads on the charpoys for us. We had green tea, some cookies, and despite it being chilly, sat outside reading, or in my case, trying to sleep. The daughter was looking after an even younger kid who obviously was a bit sickly, very shy and vaguely curious. Alain gave her a little toy car he had brought, but she seemed indifferent. Karin had brought loads of plastic bangles, and she gave some of these away also (very thoughtful of the pair of them, since they were here last year).

I may have fallen asleep – I’m not sure, but when I woke, things were stirring about. The wife had returned, with two young boys and a baby of a few months, and was making dinner. Meanwhile we were served a plate of walnuts, which we rather ineptly tried to break open using two stones. I went inside, as, though it was smoky, it was warm, and watched. She sat cross-legged by the fireside, a calm expression on her face – utterly at home. She was making chapattis, and with one motion rolling out the dough with an evenly-rounded dowel. These were laid on an iron skillet and turned often, as many as two or three at a time. When cooked, they were placed on a huge tea towel, the same towel used for drying dishes, blowing noses, carrying babies – everything. Her youngest was sitting quietly on her lap, suckling occasionally. Her husband fed the fire with dried twigs of scrub grass, and later she too did this. Another child came to be comforted, while the two little boys sat by the fire, watching intently. It was a picture to remember for a long time, peaceful and complete.

I gave the daughter my earrings as a gift, and she gave them to her mother. The mother has eight children, and judging by prevailing standards, she would have married at 18 or so. She’s probably younger than I am, and she looks almost 50!

We ate outside: rice, chapattis, fried goat (I had watched him tear a piece of cooked meat into hunks and fry these, probably a rare treat, but not for me), dhal and tomatoes, with tea and an apple to follow. Shortly before we sat to eat, a group of Germans turned up, four fellows and a girl, all students. They had walked over some pass, in snow, and were heading towards Gilgit. They pitched two tents on the roof and ate with enthusiasm the rice, tomatoes, chapattis and dhal we could not finish. Then we all sat around inside, ten foreigners and two parents, plus the four youngest children. Our group was tired but didn’t quite know where we would be sleeping. Eventually a move was made, and I ended up on a rickety charpoy in the second room, the French on charpoys outside and the parents presumably on a charpoy inside, the kids on the floor. I should have remembered bed bugs for there were lots crawling in the bedding. Between them, a very sore throat, mice attempting to eat the biscuits (the biscuits and an apple came into the sleeping bag with me), it was a less than perfect night, but I slept.

Trich Mir Hotel, 7 Sept. 1986

The morning was clear. From dawn I could hear the slap, slap of chapattis being made, and we ate our usual breakfast of chapattis, jam and tea, looking at the sun rising on Tirich Mir, the highest peak in the Hindu Kush. It was utterly beautiful. We said goodbye, and joined the jeep. The driver and conductor didn’t think much of Mastuj, as they had no place to sleep and no breakfast either. So we stopped within half an hour for tea, biscuits and eggs for them.

It proved to be the longest day. The dust was caked all over us – into our packs first of all, which are virtually unrecognizable (glad I didn’t take Renate’s pack after all). Our clothes, faces, arms, hair, everything turned a premature grey. You could taste the grit in your mouth, feel it on your eyelashes, and it continued endlessly. Nor was the terrain particularly inspiring, and besides, I think we were all too exhausted to care. Four days of that was enough for anyone. Yet I now know what a wagon west train must have been like. The road was uncomfortable too, and my throat still sore. We stopped and changed places frequently, but it didn’t help much. At least there was naan, freshly baked, for lunch, and some grapes later.

Arrived in Chitral around 2:30 PM. The first thing you see is the airstrip alongside the Majstuj River. We tried the PTDC hotel, but at 250 Rupees per night, it was ridiculously expensive. So instead, we are at the extremely basic Trich Mir, the same one as Karin and Alain stayed at last year. They had two rooms left, one with a bathroom, so the great cleanup began. It was wonderful. We drank tea (they had Nescafe too, and it seemed sickeningly strong) with the driver and conductor, paid them off, and then pottered around until it was one’s turn to wash. I’m sharing a room with Claire and Jean Louis, the one with the bathroom, and the place is strewn with hastily constructed clothes lines (at last the carabiners and slings are put to use as well as the rest of John Miller’s sewing kit!) This time I have put the cape over the bed clothes (also its first use), although I’m not sure if this place is quite so low as to have bed bugs.

Jean Pierre and I went to check out the Pakistani International airline office – no help there whatsoever, so perhaps I’ll spend tomorrow looking into it. The bazaar looks busy, interesting and full of Afghan refugees in a sort-of turban, as distinct from the flat Chitrali cap that Alain wears. We lie around in the room, Claire studying Spanish, Jean Louis reading, and me writing. Earlier Jean Pierre and Alain were having a conversation about places to travel, and Jean Louis and Claire have been all over – Yemen, Bali, Seychelles, Malaysia, Indonesia, Thailand, Nepal, North Africa, Egypt – a very well travelled pair. I still like the idea of Burma, Nepal (the Annapurna Trek), Tibet, Bangkok, some places in Indonesia, even Egypt. C’est pour l’avenir. Maintenant, je commence de penser en Francais, aussi que parler. C’est un peu epuissant, mais tres bon!

Chitral, 8 Sept. 9 PM.

The electricity is out this evening (as was the telephone this afternoon and also the water), and so I sit in the dining room by the light of a pressure lamp, at the dirtiest tablecloth I have ever seen (here comes another upsurge of American cleanliness). We ate well last night – chicken curry, potato curry, naan and green tea, and always one of use produces a treat of some sort – dried fruit or nuts or a bar. For our four-day expedition, it cost only 115 Rupees each, to eat and sleep, a grand total of $6.50! Mind you, it was never luxurious, but it is hard to believe that one can live so cheaply anywhere. Bibi, a Swiss heavy chat smoker, joined us for a game of dice, and we went to bed. Slept very poorly, and was either too hot hiding from mosquitoes, too cold under the shalwar kameez veil, or unable to breathe well with a very sore and dry throat.

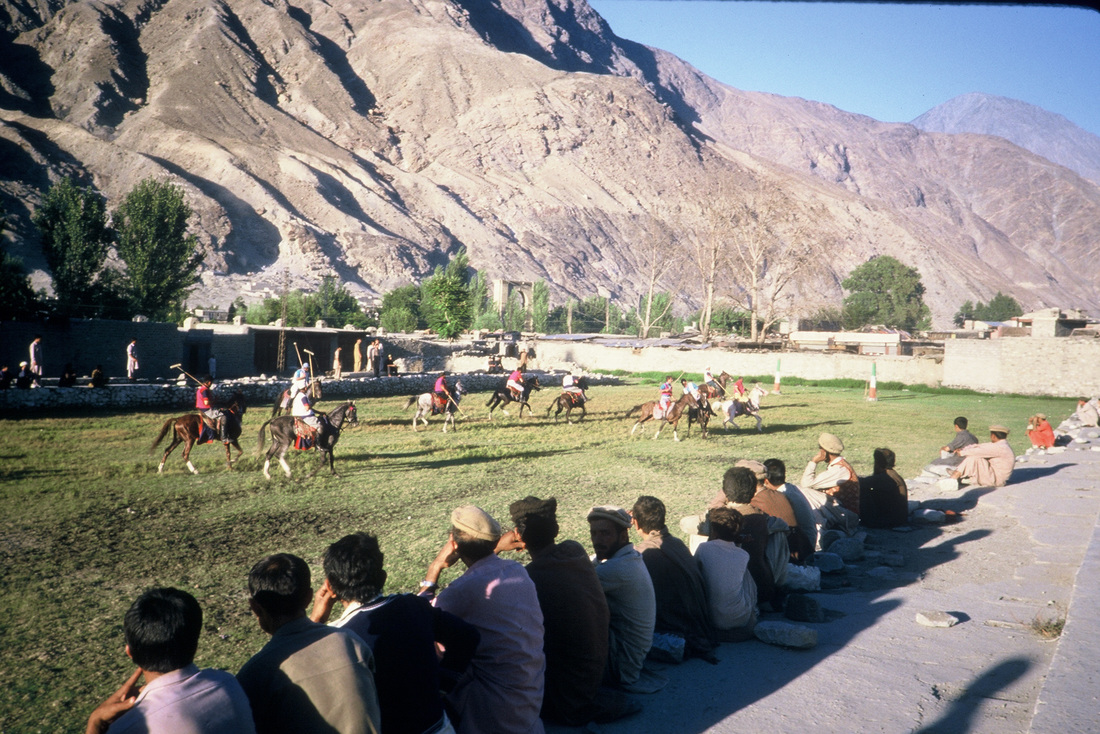

This morning I was determined not to move for the day. So I had a leisurely breakfast after the others, in the garden (2 boiled eggs, toast and marmalade – great!) and then went off to the Tourist Office to see what I could find out about going to the Kalash Valley. First visit was to the Police Station where I got the piece of paper that allows me to stay in Chitral. The Police superintendent must have been curious this morning, for he interviewed me and gave me chai too. He was extremely articulate and interesting about the area, road construction, populations, level of education, climate and activities in Winter, even about polo at the Shandur Pass this summer. Chitral won for the first time in seven years! I told him that I planned to leave on Thursday, and he said that if I had any problems, to come and see him. Next came the Deputy Commissioner’s Office for the permit to go to Bomburet for a night. After that I squatted on the floor of someone’s shop in the Bazaar and bought some gems. Then to the PIA office, an absolute joke, where they told me that I might be able to get a flight on Wednesday or Friday, but definitely not Thursday. Foiled, I thought to try the Police Commissioner at his word, and returned there. Suffice to say he told his deputy to buy me a ticket on Wednesday for the Thursday flight, and to deliver it to me at the Tourist Inn Hotel on Wednesday if I do not collect it beforehand. Even if it all falls through and I have to take the bus, it’s a great story!

It was pretty hot, even with a shalwar kameez, and I sat in the garden awhile with the others. None could get a flight so Jean Pierre and Claire will leave on a very early bus tomorrow morning, and Alain and Karin the following day. Chatted to Bibi about his lifestyle and heroin addiction awhile. God! That was depressing. Slept a little. We ate dinner here again, the same as last night, with the addition of dhal and vegetables (okra?). Sorted out the finances, and this place came to 125 rupees for two nights, two dinners, breakfast and several teas. It certainly helps to share a room. Nonetheless, I’ll go solo for the next week. So tomorrow I go to Bomburet for a day/night by taxi-jeep. It will be strange being on my own again, but it is time and I’m almost looking forward to it. Looking forward to Peshawar very much too.

Peace Hotel, Bomburet. 10 September, 1986

I sit here, eagerly awaiting a vehicle to take me back to Chitral, and the start of the long journey home. Suddenly that has come to me, that from this incredibly remote village in the heart of Nuristan, or Kafiristan, I am going home. Yet home is not Wisconsin, nor America, nor even the cabin. It is the place somewhere within me, wherein I feel I belong. It happens to be a cabin in a remote corner of Wisconsin, that’s true. But that’s not the important part. I am ready now, willing, and anxious as well as happy, to go home.

Bomburet was needed in a certain sense, for it combined the worst and the best of any solo enterprise. I was sick there, and felt as if I would never find my way back to the world. I worried too, that I might truly be ill and not just temporarily indisposed. Vomiting, sleep and no food put an end to that.

Woke yesterday morning feeling less than good, while Jean Louis and Claire made an early departure. Went back to sleep and had to force myself to get up around 8 AM. Had tea, nothing more, and donned my pack and headed up the street to the place beyond the bridge where taxi jeeps depart from. There was a Toyota truck filled with people and going to Bomburet. I planned to wait, but they said there was one more place, and I sat in front on the outside. (Good location. Remember that one, Mary!) Beside me was Dr. Susman from Ayun who had come in on the plane from Peshawar that morning, and he was both interesting and pleasant. He told me about the hijacking of the Pan Am plane at Karachi airport, and the outcome of that. He pointed out the Afghani refugee camp on the outskirts of Chitral, which made me realize that Bomburet is only a day’s walk over the mountains to Afghanistan. The Toyota was fairly new and a buzzer inside indicated to the driver (couldn’t have been more than 17) when to stop and go – very sophisticated! The doctor got out at Ayun, offered me tea but I declined (and I suppose had I accepted, everyone would have waited for me too). We stopped there to load on a lot of supplies, and then continued onward. We were also joined by an obnoxious policeman, who rubbed his legs up against me – ugh! By the time we got to Bomburet, I’d have taken any hotel just to get away from him, which is why I first checked into the Hilton. What a classic misnomer. But back to that later…

Joy, bliss and incredible pleasure! Here I sit on a chair in my palatial bedroom, having just washed in hot water (granted from a bucket), drinking tea and looking out through real windows at a wet day. I’m at the Mountain Inn, and as it is described in the guidebooks, a well-deserved treat! This place has a rug on the floor (last night’s was dirt and dirty), sheets on the bed (usual probably bed-bug ridden cover, protected by my Kelty poncho, I hope). It has curtains (wooden shutters over wire mesh), and is bright with windows. It has a fireplace, a wastebasket, and a couple of tables. But most of all it has an English bathroom complete with towel and soap. I’m in heaven, and don’t intend to budge except to go briefly down to the police station to see if they have succeeded in getting a ticket for me. As both flights today were cancelled, I doubt it, but don’t mind the prospect of a bus ride so much tomorrow, actually. It’s amazing how tolerant a clean body makes you! And so, I sip tea and gingerly eat some plain biscuits to see if I’m really back to normal.

Back to Bomburet. Sure enough, and stupidly enough, I was bamboozled into this dreadful hotel, the Hilton. The room was filthy, just vacated (by a Punjabi judging by the mess on the floor) and cost 10 Rupees. But I was too sick to care. Tried eating some tea, cake and an apple, and then went for a gentle walk. But I ended up sitting on some rocks down by the water’s edge, exhausted and miserable. Walking farther, I saw some people sitting in a garden, foreigners, and wished I had persevered in going to that hotel. Still, it wasn’t too late to change, so I gave the Hilton 5 Rupees for the tea and trouble and walked very slowly back up the hill. Wazin at the Peace Hotel was delighted to see me and installed me in a room almost identical to the one I had, also for 10 Rupees, but as someone (the American female, my predecessor) had dropped a bottle of Dettol there, it actually smelled clean. Wazin assured me there were no bed bugs, but I don’t believe anyone any more. I slept a while, woke, and felt worse. Finally I vomited and felt very much better. Wazin came in to chat a while, and even knocked first. He wanted to talk about women, sex, birth control, pregnancies before marriage, older women and younger men - all those good, non-Islamic things. So I talked with him awhile and told him that I liked men my own age – he’s 24! Actually, he was insightful into some of the realities of life here. For example, just as in Tunisia, it’s expensive to get married, about 25,000 Rupees. He didn’t like his parents’ choice and so is holding out. I think he dreams of becoming some older woman’s gigolo and going to Europe with them for a few months, or getting to know some foreign woman at his hotel over a 2-3 month period. While I could never have imagined any non-Islamic woman adapting to a life like this, he told me of an Australian woman who met a man up the valley, returned the next year, married him and now lives here with 5 kids. I would very much have enjoyed meeting her and talking about it as a lifestyle. What motivated her, I wonder?

Bomburet was as described – the women beautiful, perhaps just because I could see them, with many long, skinny black braids, and a colorful head-band or even the more elaborate head-dress with the cowrie shells on some of the older women. The feeling in the valley was one of contentment, even on men’s faces, who no longer had that agonized or disgruntled or hunted look. People smiled readily. In ways it was like Hunza, but more relaxed. I passed three men, all with guns, walking down the jeep track. They looked cheerful, as if coming from a day’s hunting in the mountains, and smiled at me as an equal. What a change. But they could just as easily have walked the same day over the mountains from Afghanistan, so close is it.

Back in the garden, even the dogs and cats looked comfortable. And there was an English couple, late 30’s, the man returning after 19 years to Bomburet. He was marvelous, and indeed I enjoyed both their company very much. They too were bamboozled into staying down the road at the Hilton, but stayed for (an excellent – I believe, I was being careful of what I ate) dinner, and planned to move up here the next morning. When he had been here before, there were no hotels so he stayed in the rest house. There was no road either – they walked over the hills from Ayun. In 1967 that was quite an adventure. She travels a lot as a computer specialist at Oxford; he’s an Accountant. I could happily have chatted to them all evening, but we parted with them borrowing a lamp from Wazin, to be returned the next day. He also told them to pay for dinner the next day. Really, it’s a very trustworthy country, at least up here.

I asked earlier where the toilet was, and be told: “everywhere is toilet in Bomburet”. Before bed I asked where to go, and Wazin inquired “small or big toilet?” Fortunately it was 'small' because he pointed to the semi-constructed new wing of the hotel. If the occupants of the future only knew what solid, dry foundations they slept on!

It was cold, but I slept well and woke around 6 AM for the 7 AM jeep. Needless to say, it left around 8:30, crammed with people. It was a Toyota and I was in the back, first spot. No cushions, so it was hard on the old arse for two and a half hours back to Chitral. Two Japanese were also in the back. This time I was interested enough to look around, and noticed the houses more. Mine (at home) is a rock, a stone mansion by comparison with theirs. Yet they are beautifully constructed with the wood and stones and mud that is available.

Close to Chitral we passed about 4 or 5 refugee camps. I had read about these: how the first arrivals got tents. Gradually they built walls of stone and mud around the tents and used the latter as roofs and awnings. Some of the tents bear the names of their benefactors. I expected to see only old men, children and wounded, but there were many healthy young men, some carrying the infamous Kalashnikov or some other gun. So I wonder are they just taking a break from the resistance, or what? Still, life seemed to be going on in the camps as in a North West Frontier Province village anywhere, so they didn’t seem depressing only inasmuch as they reminded one of what’s going on.

It’s pouring rain. Some of the Germans from Mastuj are here, sick. There’s a couple of English planning to go over the Shandur Pass. It looks like it’s going to be a pleasant, wet afternoon. Hope it clears eventually, though. I’m not so lucky with catching planes.

Habib Hotel, Peshawar

12 September, 1986

I joined the Germans to go and watch polo, but instead there was hockey and cricket. Mind you, the adjacent playing fields get quite a work-out. All males under the age of 30 seemed to be there playing some sort of game or another, right down to running with sticks and wheels. The Germans went off to buy food for the trip to Gilgit – they had hired a jeep with a couple of English as far as Teru. Back at the hotel there was a scruffy wee Australian chatting to the manager, and I began to talk with him. He was Julian, a home economics, agriculture and horticulture school teacher from a big Irish family somewhere near Victoria, and we hit it off grand. We chatted for hours through dinner, and I was sad to see the back of him, sorry not to be staying longer to go fishing with him ‘cos he would have been a lot of fun. He’s right: Australians and Irish get on remarkably well together! Without much appetite, I ate in the dining room, a delightful, lofty and almost grand room with a big fireplace, beams, and an Ibex horns over the mantle. Bird songs in the garden were beautiful and it seemed ridiculous not to be able to enjoy an after dinner drink by moonlight. Stupid law! During dinner Karin called and said they had decided to go tomorrow to Peshawar by bus. Earlier they had come by looking for someone to share a jeep to Dir, and I had agreed, with two other Pakistanis for 1000 Rupees, but they were subsequently told it was much too expensive, so I went for the bus idea too. Called Tom and arranged to stay on Sunday night before I leave with him and his wife, and asked him to confirm my flight.

Slept very poorly (probably bed bugs in my bed or in the sleeping bag from the charpoy at Mastuj), and I was congested and even cold. Woke at 1 AM and couldn’t get back to sleep again before getting up at 4:45. Walked down through a very deserted Chiltrl Bazaar to the Tirich Mir View Hotel to find Karin and Alain. They had great stories of meeting a mujahadin the night before, here for two months, from Afghanistan, to get supplies and then return, an impressive figure by all accounts and a little Asiatic-looking. I have seen similar men in the bazaar and it is true, they have a certain air. Alain had a photo taken at the Afghani photograph boxes, and the result, in Afghani head-dress, was unbelievably authentic! He’s a riot.

Life began to stir: smoke from chai samovars and chapatti ovens, dogs ceasing to roam and play in the streets, shadowy figures squatting by the drains and taps to wash, stirring blanket-clad lumps on charpoys. At the bus station our driver was cleaning the windscreen of our bus, and beckoned for us to put the bags inside. We had the seat behind him, all three of us. I’ve never seen quite such a bus. It was truly remarkable. In the 1950s I suspect it had been a Bedford, but was by now so stripped of its parts that identity seemed immaterial. Unadorned, it seemed even more of an anachronism. All the windows had been replaced with marred Plexiglas except the windscreen, which came from something else, and was curved so that no wipers could ever clean it. Needless to say there were no wipers! Nor were there any dials, switches or lights, although the auxiliary horn actually boasted a push button (instead of our jeep’s driver who used to touch two wires together). Suspension was absent too, as we were later to find out.

We sat briefly in the waiting area among charpoys full of sleeping babies, refugees, praying Muslims, and then got chai and cake before our departure (to the sounds of the morning’s hawking and spitting). The driver had said his “Inshallah” with zest, and drove correspondingly. He was a fiend, cursing, upbraiding slightly slower vehicles and people, in fact anything and everything that stood in his way of getting to Dir by noon (6 hours). Mind you, the Lowari Pass at 10,500 ft. didn’t seem to faze him in the slightest. He was incredible, as was the bus, but it was a bone shaker. A pity too, as leaving the Chitral Valley along the opposite bank of the Chitral River as the one we took going to Ayun was magnificent. Tirich Mir was slowly unveiling itself for another hazy day, a brief view of her beautiful face like a Muslim woman. The valley was green, with a broad sash of riverbed wandering through – it was the loveliest, lingering view of that valley I have had, but impossible to photograph. Occasionally, forts stood overlooking the river, guarding what I do not know. But Alexander the Great was here too, they say, so maybe they remembered they could be invaded. Every few miles, it seemed, there were refugee villages, now with fewer walls than tents, stockpiles of firewood were piled beside them, and only women and children to be seen. As we went higher, the road deteriorated to an avalanche bed, with huge scoured and scrubbed pine logs scattered around, or shattered into fragments, by avalanche or refugee, it was hard to say. Tiny gardens dotted the inhospitable land, and yet more tents, and hastily erected mud dwellings: the doors and window frames and built-in shelves standing first, to be filled in later with stones and mud. Winter will be rough on them. The country-side becomes Alpine and the road more precipitous – once we had to do a 3-point turn, and many times we waited for laden trucks to squeeze by the bus. All trucks from Chitral seem to leave empty, for what is there to bring south? At the near side of the pass we stopped for chai and me for a piss – difficult to find privacy, so I dropped trow, and no doubt shocked some unsuspecting native. Tough! At the top of the pass there was a passport check. So, in rain and cutting wind we entered this hut where the authority was huddled under a blanket by a fire, along with a few others. The bus waited coldly, I’m sure pissed at our presence and the delay we caused. The far side of the pass was more desolate, less precipitous, with as many scattered tents, and huts farther up hillsides. I had always imagined the Hindu Kush to be lonely, but not so. People exist everywhere, even there. It’s humbling to consider how utterly incapable we would be of surviving here with what is available. Yet they have, for a couple of thousand years, without change.

Dir was bustling and enthusiastic, with lunch being served tantalizingly, everywhere, at 12:30. We rushed onto another bus, squashed in with people, goods and even chickens, heading south to Peshawar, as we thought. We had paid 40 Rupees for our last bus. This was 25 Rupees, so we were way ahead of the jeep and half the price of a plane. Still, by this time I’d have given a lot for the plane! We passed villages with people casually toting guns, in flatter, more fertile land. This time we stopped by a mountain stream pouring into the Panchkora River, for the Muslims to say their prayers, and this time for me to piss in peace. This driver also went at breakneck speed, and it was sleep or be sick, fortunately the former. Now it became hot, dusty and uncomfortable as we meandered through the southern Swat Valley, more built-up, less interesting, more populated. Buildings everywhere looked decaying, even the ones being constructed from local bricks – we passed several brick works near Mardaan. Maybe they don’t have the right soil, the right mix, but the bricks themselves looked decayed also.

Mardaan bus station was a treat. There must have been 50 gaily-painted vehicles there, each with its conductor shouting the destination over and over again. Little kids came to the windows selling pomegranate juice, food, anything. Beggars too. And we were rapidly taken by our conductor and consigned to another bright piece of decrepitude with 15 Rupees (5 R each, I presume), for the last haul to Peshawar. Haul it was, for we were on a local bus. But I think all buses are local, stopping at every raised hand, every request. We had missed lunch, dinner, and were now looking forward to a repast of figs, nuts, dried apricots and digestive biscuits with iodinated water, our combined resources! Arrived around 8 PM and got a horse and cart for 15 Rupees to the Habib Hotel where we saw Jean Louis and Claire’s names on the register. We found them in the dining room and had dinner from an enormous menu, though I wonder if everything was really available. Soup and mixed grill with chicken was just fine, with 7-Up too! I was delirious with sleep by then and fell into bed, hot and muggy, dirty too, but I didn’t care.

Slept well, despite noise and unfamiliar city sounds. The hotel is pretty tawdry, although it’s an imposing 4-story building from the outside. The banisters are painted in three pastel colors, and the unfortunate adjacent cactus has been painted (disfigured) in matching shades. Do cacti have pores? It seems not, or like Goldfinger, this one would suffocate. It stands there in the corner, bashful and embarrassed. The room itself is a tribute to plastic: naugahide and formica and linoleum. But there’s a fan, a mirror (I’ve not had one in most places, and never one in which I could see more than my face, since day one. I’ve lost weight), and good water pressure, and a flush part to the squat toilet. Despite there being only cold water, it’s fine ‘cos it is too hot to take anything but a cold shower in any case.

Karin and Alain stopped by to go to breakfast and we ate with Claire and Jean Louis also: cornflakes and hot milk. Joy! There was even butter, which I’ve not seen in 3 weeks. After breakfast we headed off to the jewelry bazaar, only to meet the carpet seller on the street. He persuaded us to go to a friend’s shop, and there we sat on carpets on the ground, drinking tea, eating nougat, and looking at jewelry. It was thoroughly entertaining, particularly as I had no urge to buy anything. But Jean Louis and Alain did, and so our two hours there were not in vain, although I think they enjoy the ritual of selling as much as the actual sale itself. Next we went to another friend of the carpet seller’s and there looked at older, more ornate and ceremonial jewelry. We had fun, trying it on, and posing in it for photos, and there I did buy some things. The building the carpet seller is in is full of Afghani, and there used to be a carpet “factory” with young boys doing the work, on the roof. But a bomb or a bomb threat ended that. During the day I heard many different things about Afghanis, the refugee problem, mujahadin, relief organizations and relief, and at the end I’m confused on many points. So maybe it’s best to withhold any opinions until I find out more. Certainly the people here, Pakistani people, are different to Chitralis or people in Hunza. First of all they are more devout, although today is their Sabbath and they are a little more fervent just today, I imagine.) The hotel room looks down on a mosque and I can see men salaaming. Little do they know there’s a naked Irish bird examining them from above.) Tonight I tried on a chador, the headdress with the little grille to look through. It was claustrophobic as hell in there, but what marvelous anonymity! It would be fun to walk through the bazaar wearing it. As it is, a shalwar kameez is no help as mine has shrunk, is ridiculously short now, and with a crop of fair hair above it, looks no doubt even more ridiculous! It was stupid to have shortened it before washing – I should have known better, as this hardly the land of pre-shrunk garments.

Walking the streets of Peshawar, while they are fascinating, is a nuisance, as Vespa rickshaws are always pulling alongside to see if you want a taxi. Then adolescents, in packs of course, harass you too. Everybody stares, but they are a little more aggressive. Still, it’s pretty innocent. But it’s no place to stroll if you want to be left alone.

I had a farewell glass of pomegranate juice (no ice, no water, no sugar) with Jean Louis and Claire, and headed off, walking towards the old British Cantonment along the Mall. It’s as the guidebooks describe: wide streets, nice bungalows behind gates, fences and walls, gardens – all shades of ancient glory. Had tea at Dean’s Hotel. I had to go to either it or Flashmans in ‘Pindi to get an idea of what colonial life was like. While updated somewhat, it is built as a sprawling bungalow in a big garden, and the inside is cooled by many ceiling fans. There were ornate ceiling lamps and some brass, but otherwise fairly unpretentious. A deserted Bar, now boasting a telephone only, had seen better days, and there should have been a piano too. Looking around and eavesdropping, I spied what I thought was an old English Colonel, except he was dressed like a Pakistani. But he barked out his request for chai, and proceeded to pompously sit down and read his paper. It transpired that he is with some American Afghani aid group, a film producer! There are over 40 aid organizations represented here, and I wonder how many of them use half the money to stay in Dean’s Hotel, act colonial, and discuss the problem.

Val is right about pissing. Here they piss everywhere, but further north they seemed more circumspect, or maybe it’s just easier to find good spots in less-crowded cities.

Went to the Peshawar Museum, which reminded me of the Dublin one – uninspiring and uninspired, except for the stuff on tribes, and even that was scant. There were a few Pakistani women in a group there, the rest schoolboys, and a couple of soldiers holding hands (as so many men do here). Homosexuality is accepted by Muslims, and I always thought it was of necessity, not choice….would there be as many? Someone tonight at dinner, a French Pathologist working here, said he saw many married older men still homosexual, even with 2 wives.